Introduction

This piece is part 1 in a two part series on the Vorschlag and the Nachschlag.

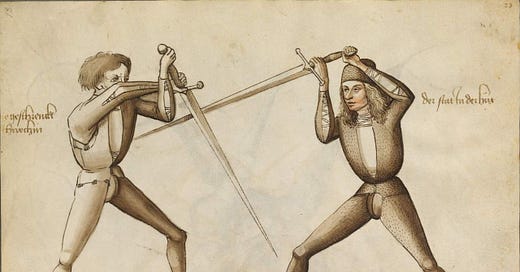

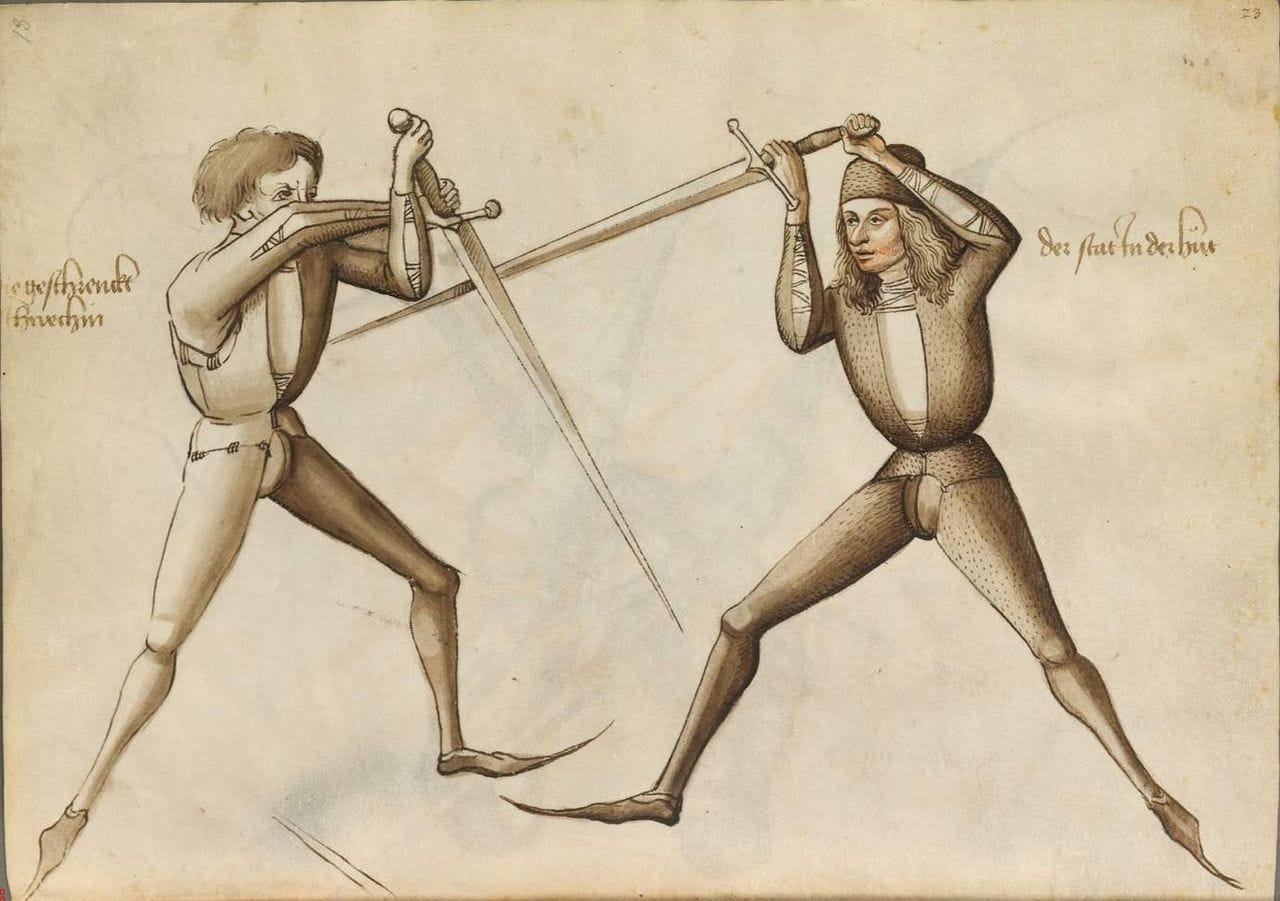

Within Liechtenauer’s Kunst des Fechtens, Ms3227a is a unique document. It seems to approach Liechtenauer’s KdF with a different style than the RDL (Ringeck, Danzig, Lew) texts do. One of its central unique teachings are the tactics of Vorschlag and Nachschlag, the Leading Strike and the Following Strike.

Within the online discussion circles of HEMA, I feel there is a need for an updated interpretation of the Vorschlag and the Nachschlag. It has seemed to me for some time that many HEMAists have a view of Vorschlag and Nachschlag that is very one-dimensional, and not consistent with the overall teachings of the Codex or its principles.

The “typical” view of Vorschlag and Nachschlag I encounter in online spaces like Reddit, Facebook, etc, is that the Codex is calling for a constant all-out offensive. Attack first, attack hard, keep attacking, no mercy.

Put into practice, this often results in HEMAists blindly charging into each other and double-hitting as if in a mindless peasant’s brawl, to quote Joachim Meyer,

I think this interpretation is limiting to our fencing as modern KdF practitioners, and is based on a fairly shallow reading of the Codex.

So, for the sake of clarifying my own understanding and hopefully to expand the knowledge of other fencers as well, I embarked on a written analysis of Vorschlag and Nachschlag.

This project swiftly proved much larger than I anticipated, growing like a weed until it was absolutely impractical in length. At that point I decided to divide up one article into two parts.

Now I know that fencers are often an impatient breed, so this first part will be the “executive summary”. In this piece, we will discuss the overall “model” for how I think Vorschlag and Nachschlag should function in its general principles, how it should be used in fencing, and some points about how to train these tactics.

The second part will be more on the technical side, for those of you (The “four or six” of you) interested in such. It will be an examination going through all the textual references to Vorschlag and Nachschlag within Ms3227a, to illustrate the textual evidence from which I derived my current understanding. It will use a “text and gloss” format, similar to what I did in the “Principia und Pertinencia” piece, in which I quote the passages of the original text and then discuss my interpretation of them, paragraph by paragraph.

What is a Vorschlag?

The simplest answer is “the lead strike” of the engagement with your opponent in fencing. But there’s a bit more to it than that.

Let us approach the Vorschlag by focusing on what we’re aiming to achieve with it. Let’s focus on our goals first, and think about mechanics later.

What do we aim to achieve with the Vorschlag? We are looking to gain advantage over our opponent. How shall we define advantage? Well there’s two ways to go about that.

The strictly textual interpretation, based only on the text’s explicit statements, is that the advantage of the Vorschlag lies in inducing the opponent to parry. Either the opponent gets hit, or they parry, and in the moment they are committing to parrying we are both safe from them attacking us and can proceed to our own following attacks in that moment of safety.

That is one possibility. The other possibility requires taking into consideration some of the Codex’s other statements in the Zornhaw and Twerhaw glosses and the text of the Vorsetzcen. If you consider the Vorsetczen as a valid form of Vorschlag (I initially thought it was, now I think not so much), then we could also say that moving into a favourable position or bind of blades may also be the advantage of the successful Vorschlag.

What do I mean by a favourable position? A position in which firstly we have some defensive security against a direct attack from our adversary, and secondly we are positioned to make our next strike on a shorter or more direct path to the opponent’s body than the opponent must take to reach our body. There are many variations of this, but generally these positions are identified by having our opponent’s blade on the outside of our blade, and by positioning ourselves to be able to reach the gap or space in between the opponent’s blade and their body, with our body collected and prepared for launching our next action.

That is admittedly a stretching of the text, and perhaps insurmountably so. When I embarked on this project, I felt quite certain that this was a very important point. Later I received some cogent criticisms from several people whose opinions I respected on the matter, and so now I am less sure that this matter of positioning is critical to the Vorschlag, or that one can indeed “win the Vorschlag with Vorsetzcen”. Such is the nature of HEMA textual interpretation. I leave this matter to your judgment, reader. For further discussion, refer to the “To Vorschlag or Vorsetczen?” section later in this article.

The Vorschlag is supposed to proceed seamlessly and smoothly, without hesitation or delay, into the Nachschlag. To me this suggests implicitly that the completion point of the Vorschlag will lead us into or prepare us for the Nachschlag. I do think that even in a more strictly textual interpretation of the Vorschlag’s advantages, positioning yourself and your blade for launching the Nachschlag can be considered as one of our objectives.

Importantly, the Vorschlag is supposed to be to our advantage whether we hit or miss.

If you go all out with a direct attack that, if it fails and is parried, delivers you into an opponent’s crushing riposte, then you are not doing the Vorschlag correctly.

This tactic does not rely on certainly landing the hit no matter what, but on winning the advantage regardless of whether your strike lands or not.

Offering a realistic threat of a direct attack on the opponent’s body is one way to win the Vorschlag. Cut or thrust, the actual mechanical action chosen does not matter much. The important thing is that you get the opponent into a defensive mode.

Most usually, I think this requires an attempted direct attack, but with particularly nervous or defensive opponents you may be able to induce them to parry merely by preparing with sufficient aggression.

If you successfully make the opponent defend, then you are forestalling them from being able to strike at you in safety. If the opponent is committing to a parry, then for the timeframe in which they are moving into that parry they will be temporarily unable to easily strike at you, and you will have a window of opportunity in which to strike them or to continue to move in and gain a better position.

These are our objectives, now how to do it?

The first practical consideration is distance. The Codex tells us that the Vorschlag is launched when we can reach the opponent with one step, but does not tell us whether this means a big step or a small step. It also says in regards to the use of the point that one can hew or thrust “to the point”, which I interpret to mean attacking where one can place the point against our opponent at our full reach.

Putting these things together, I would say that the textually given distance is one at which the Vorschlag can reach our opponent with the point of our sword within the course of one moderately sized step.

Conveniently, this is also a good distance from which to threaten our opponent.

We do not want to attack too far away from our opponent. At too long a distance, we are less likely to get a defensive response from our opponent as they will not feel threatened. They may try instead a more dangerous counterattack. Nor should we close distance too much without attacking. Closing distance too much without taking action invites stop-thrusts and other unpleasantness from the opponent.

Secondly, we must consider how to move towards and threaten our opponent most directly, by the shortest route. This is in part a consequence of distance. If we launch the Vorschlag from a range where we can land the point on our opponent within one step, then there is no space or time available for any extraneous blade actions. Any kind of sideways blade motion or other non-threatening action at this distance will invite exploitation and attack from our opponent, so we must act directly as possible.

This need for directness is also a consequence of our desired objectives. If we want to induce a defensive response from our opponent, we cannot leave them with an opportunity which encourages them to attack.

In connection with this, we should judge what opening or target on the opponent we can most certainly reach with a direct strike. The Codex instructs us repeatedly that this opening movement should be aimed at the openings of the opponent, their head or body, not their sword. Beating the blade may have its applications, but it is not the Vorschlag. Further, opening with sideways motion towards the blade and away from the opponent’s targets can also create opportunities for an opponent’s counterattack, or the dreaded disengage-thrust, which is again not in alignment with the goals of Vorschlag.

Thirdly, we should consider how we will follow up from this opening strike. The Nachschlag is meant to follow from the Vorschlag seamlessly, without hesitation or delay or extraneous preparation, so our position at the conclusion of the Vorschlag should be one that leads us into our desired Nachschlag.

The Codex advises us to not be too aggressive or too overly committed with the Vorschlag. We are to observe “measure and moderation”, by which it means not striking the Vorschlag so hard that we cannot smoothly Nachschlag in follow up, nor stepping so large that we cannot take another step afterwards in a timely fashion.

The advice here is that our movements should complete with collection, our body poised and ready for further movement. While threatening the opponent demands some commitment from us, we shouldn’t overly commit to such an extent that we can’t recover or make follow-up actions.

We must also consider in advance what type of engagement we wish to shape. The Codex tells us “if you're obliged to fight earnestly, you should contemplate a thoroughly-practiced play beforehand (whichever you want, if it's complete and correct), and internalize it seriously and hold it in your mind with good spirit. Then perform whatever you chose upon your opponent with pure intent”.

In other words, before we engage we should have a full plan of action in mind. Unfortunately it doesn’t tell us anything more about what that plan needs. In my own practical experience though, I think this plan generally needs:

1. An opening threat to our opponent

2. A planned follow-up attack, possibly several depending on conditions

3. A recovery action or defensive back-up in the case that our opponent manages to gain an opportunity to strike or our plan otherwise does not proceed as anticipated.

While it is important to have a plan, it is also important that the plan be flexible. You don’t want to end up in circumstances where if one little thing is not as anticipated, your entire plan is foiled. Your plan should have some pliability, some ability to adjust to changing circumstances.

This is I believe the underlying principle within the lessons on Fuhlen and Indes in the Codex: Adjusting our plan on the fly to the opponent’s actions and reactions.

A final consideration is the Codex’s instructions on concealing what we intend from our opponent’s eyes. If we walk forward with a very clearly projected intent, clear as day when and where and how we will attack, it becomes very easy for the opponent to defeat us with a planned counter or parry-riposte, which again negates the desired advantages of the Vorschlag.

The text states we should keep what we intend to perform hidden from the opponent’s eyes. I interpret this to mean the use of “concealing actions”, an uncommitted shifting pattern of motion of blade, body, and feet which make it difficult for the opponent to pick out our exact preparations or when and how we will attack.

To summarize:

The Vorschlag is an opening action, which begins the engagement.

It aims to gain us an advantage, whether we succeed at hitting or not.

We aim to induce the opponent to defend while also preparing our follow-up strike.

We throw the Vorschlag at a range where we can reach with the point, by cut or thrust, with one step, in a direct movement by the shortest path.

We aim for the opponent’s openings, not for their sword.

Our action is committed enough to threaten, but not so committed that we can’t keep moving afterwards with further blade actions or footwork if needed. We should complete with collection, ready for further movement.

We conceal our intentions from the opponent, to generate surprise for our Vorschlag, thus to more surely induce a defence.

We engage with a plan in advance, while also remaining flexible to changing circumstances.

What is a Nachschlag?

Having gained an advantage with our Vorschlag, the Nachschlag or following strike is the action we launch afterwards.

Following our same goals-based methodology we outlined above, what is the Nachschlag intended to achieve?

The first and most obvious goal is that the Nachschlag should land a hit on our opponent. Whereas the Vorschlag does not need to land, the Nachschlag appears to be more fully committed to landing a strike.

Secondarily, if the Nachschlag is defended then we should be able to use it almost like another Vorschlag: So long as the opponent continues to commit to defending rather than attacking us, we can continue to throw more Nachschlage. If successful, this continually forestalls the opponent from taking the offensive, and will eventually overcome their defences and land a hit.

Thirdly, in my opinion the Nachschlag has more of an explicit positioning aspect attributed to it than the Vorschlag does. The Codex describes “following” the opponent with thrusts or cuts if they try to escape from the bind with your sword, positioning yourself closer and closer to them even if they continue to defend.

So, our goals for the Nachschlag are to strike our opponent, or if that does not succeed then to to keep them defensive while continually improving our position to strike them by the shortest and most direct paths.

How shall we achieve this? The text provides several key points.

The first is the matter of timing the Nachschlag. The Codex states that the Nachschlag should be thrown instantly, as if in one thought or one motion with the Vorschlag. More specifically, it tells us that we should move on to the Nachschlag as the opponent defends.

The distinction here in my opinion is that we wish to be launching the Nachschlag while the opponent’s parry is still moving or committing momentum into defence, not when the opponent is beginning their own riposte. The advantage to this timing is that we move into our following attack as the opponent is still parrying, so we are acting with the advantage of being a beat ahead. As with the opponent’s parry forestalling them when we win the Vorschlag, we have a window of opportunity of safety created by their parry to move further in and strike.

Another consideration of timing is that it is often best to throw the Nachschlag when the opponent has defended in a late and rather panicky or unready fashion. This is the ideal outcome of achieving surprise with our Vorschlag. An opponent unprepared for defence may parry in a heavier or wider fashion, thus giving us a larger opening for launching and succeeding with the Nachschlag. Wanting to induce a late, instinctive, and panicked parry is why surprise is desirable for our Vorschlag.

As with the Vorschlag, the text also specifies that the Nachschlag should be thrown on as short and direct a path as possible, targeting the closest openings we can most surely reach by the most direct route.

This is beneficial firstly to our desired timing: On a shorter path of attack, our Nachschlag takes less time, and thus can more successfully target the opponent as they remain defending.

Secondly, a short and direct Nachschlag affords the opponent less time and less opportunity in which to try to develop a riposte, and thus also is beneficial to keeping them defensive. This requirement for short, direct movements also implies that wide movements or extra preparatory motions should be avoided.

Ms3227a gives us two specific suggestions for what kind of Nachschlag to throw, depending upon the opponent’s blade actions and presence in the bind.

The first: If the opponent is Strong and Hard in the bind, pushing our blade aside, then we are to withdraw from the bind, let their blade go, and then strike them to the next closest available opening created by them exposing themselves by pushing their blade to the side. The most prevalent version of this in HEMA competition and sparring is probably the “strike around” with the Zwerhaw1,

This strike can aim at the head, flank, arm, or hand depending on distance and the opponent’s commitment into the close of measure. Another option I have found successful in this situation is a fairly tight, vertical cut over aiming at the hand, wrist or forearm, something akin to Fiore’s cut over from the crossing at the points2.

Second: If the opponent is Weak and Soft in the bind, in a position of weaker leverage or preparing to leave the bind, we are to drive directly in with a thrust to the face or chest.

Importantly: If the opponent is Weak in the bind, don’t chase their blade and push it aside as this would open us for the same attack on a new line as we use when the opponent is strong in the bind. Instead, drive in direct by the shortest, straightest path. Usually this will be the thrust, although the Codex also admits that targeting whatever you can reach with any attack you can most directly do is also an option.

Here the thrust from the bind comes after a parry, but a similar action can be applied to the Nachschlag

This pair of options feed well into each other as well: If the opponent parries aside your attempted to thrust through the bind, then they almost necessarily must become Strong and Hard in the bind to do so and exert lateral pressure and leverage on your blade. If they do so, then firstly they will further forestall their own attacks, and they will frequently expose a new target for another strike. This need for lateral motion and the use of Strong and Hard leverage and pressure to offset thrusts is part of why the “Fleche to Zwer” combination is frequently seen throughout HEMA competitions.

Fleche into Zwer, one of the most prevalent Vorschlag-Nachschlag examples in modern competitive HEMA. 3

There are of course many other potential Nachschlag one can throw, depending on the particular nature of your Vorschlag and how your opponent responds to it. This vast potential variety is acknowledged in the Codex, which tells us to target the opponent by whichever opening and target is closest, and by any means of striking (Cut, thrust, or slice).

To summarize:

The Nachschlag follows out of the Vorschlag, smoothly and seamlessly in one flow.

It aims to hit, or to keep the opponent on the defence if it does not hit.

We aim to time this strike ideally as the opponent is still in the process of defending and has not yet thrown their own strike.

We target the closest opening we can reach most surely, by the shortest and most direct path. We should avoid wide and slow actions or extraneous preparatory motions, anything that may delay our follow up or give the opponent time to develop an attack against us.

The tactile feedback of blade against blade is used to inform us what Nachschlag we can best throw: Against weak pressure or presence in the bind, drive in directly. If they give strong pressure, pushing our blade aside, target a new opening.

Cut, thrust, or slice does not specifically matter, any can be used for the Nachschlag.

Vorschlag, Nachschlag, and Schütczen

A common line of criticism I have heard towards Ms3227a and fencing according to its precepts is that the Vorschlag and Nachschlag leads fencers to an overly aggressive style.

As the critique goes: If a fencer tries to use Vorschlag and Nachschlag as the Codex describes, then they will charge in heedlessly to the opponent’s threats and will run into dangers like counterattacks. If two fencers try to apply this to each other, the result is constant doubles. Rather than a clean and safe approach to fencing, the critique goes, Vorschlag and Nachschlag makes you make stupid and risky mistakes. I have even heard this described as “Fencing with Main Character Syndrome”4

In strict fairness to this criticism, this is indeed a pitfall of trying to apply Vorschlag and Nachschlag. If you fixated only on the parts of the text which outline those tactics, I could see how that would be the conclusion you would reach. Risky attacks, trouble with ripostes and counters, and high risk of double hits would indeed ensue if you approached things that way.

I think a more nuanced picture appears when you consider all parts of the text.

If you read my previous piece, “Principia und Pertinencia”, you will recall that one of the fundamentals of fencing listed in that verse was “Schütczen”, a word meaning defending, covering, protecting, or safeguarding. I interpreted this word’s inclusion in the list of fundamentals as indication of the importance of defensive safety and defensive actions within Liechtenauer’s Kunst des Fechtens.

This may seem paradoxical, given that people’s views of KdF often fixate on its proactive, offensive-emphasizing nature. I believe that defence is just as important and one cannot have a complete and sound approach to fencing without it.

There are various passages within the Codex that attest to the importance of defence. We are told for instance that with the Vier Vorsetzcen (Four Parries or Four Displacements) we can deflect cuts and thrusts, and moving into the Hengen with the Vorsetzcen we can “perform the Art well” (Fol 23v)5. Likewise we are told that one who wishes to be a good fencer should first and foremost learn to turn away or ward off (Abwenden) an opponent’s blows well (Fol 36v).

Evidently, defending actions are an important part of this system. This is supported by the listing of “Schütczen” among the principia, and by the text also repeatedly mentioning the importance of caution and prudence.

Further, we are told to observe measure and moderation in all plays and rules of fencing. So while we are to be audacious and strive to take the offensive with the Vorschlag, we are still to observe moderation and not become overly aggressive.

How can we reconcile the described tactics of Vorschlag and Nachschlag with these principles of caution, moderation, and the place of Schütczen as a fundamental of the art?

There are three primary risks one runs into when trying to win the Vorschlag, in my experience.

An opponent who does not parry but rather tries to counterattack or strikes at us during our Vorschlag.

An opponent who parries successfully and is not forestalled by our attack, but rather executes their own riposte immediately before we can begin a Nachschlag.

An opponent who attacks us first and wins the Vorschlag before we can.

The third risk is already accounted for in the Codex with many techniques with defensive applications, and is relatively straightforward to deal with: Defend the attack first, then riposte with your Nachschlag yourself as quickly and directly as you can.

For this piece I will instead focus on the first two. Both of these can lead into double hits, or can be used by a skilful and cunning opponent to defeat us. What answers do these challenges does the Codex provide us?

For an opponent who attempts to counterattack, we are given a hint in the technique of the Zwerhaw. The 3227a Author is quite a fan of the Zwer, saying “no cut is as good, as honest, as ready, and as fierce as the crosswise cut.” (Fol 27v).

We are also told that it counters and defends against descending cuts, and that if we do the Zwer with our hilt and hands forward and above us, then we shall be well defended and covered by it.

Importantly, we are told that we can win the Vorschlag by attacking with the Zwer. While the requirements of the Vorschlag are that we aim for an opening and not for the sword, winning the Vorschlag with the Zwer also demonstrates that we can target an opening while still covering ourselves or taking opposition against an opponent’s lines of attack. This is still not an action directed at the sword, the movement should primarily be directed at threatening an opening but is delivered in a way which crosses or occupies the opponent’s lines of direct attack.

It is an open question whether this covering feature is unique to the Zwer under the Codex’s understanding (This would explain why the Author thinks the Zwer is so good), or whether this feature can be generalized to any Vorschlag. The text’s general approach to Vorschlag is that it is a broad category of tactical actions, not limited to specific mechanical techniques. I would say there are some ways of doing Vorschlag which may use opposition, such as a Zwer Vorschlag, and other ways which may not use opposition and yet still can be a functional Vorschlag.

The Schielhaw is an example of a technique which goes directly to the opening with the point while also creating opposition against an opponent’s lines of attack6. In this next example, I hit directly, but one can also take the Vorschlag with Schiel drawing an opponent’s parry.

It is also worth noting that delivering a Vorschlag with opposition only really solves the counterattack problem if the opponent is attempting a direct counterattack, delivered straight from their starting position. It does not work nearly so well if the opponent instead relies on unpredictable indirect counterattacks (I.e: A counterattack on a different line than their direct line of attack).

These attacks, delivered into your Vorschlag, will very often result in a double hit. They’re also quite hard to stop as the attacker in the moment, nigh-on impossible in fact. A defender, however, also should not be acting in this way, as it makes them receiving a hit nearly inevitable for themselves.7 It is very difficult to account for an irrational opponent in fencing.

With opposition, we can win the Vorschlag and still be covered against at least the majority of sensible counterattacks. What about the problem of the riposte?

Now as per the text, if we win the Vorschlag and perform the Nachschlag correctly, then the opponent should have no clean opportunity in which to riposte.

A lovely ideal, yet any of us who fences know that often that’s not what occurs. An opponent who has made a parry will be striving to get to their riposte as quickly as they can. This is particularly the case with trained and skilful opponents, who will attempt to parry in a way which sets up a direct riposte as fast as possible.

Some examples in demonstration and in competition of how a fast riposte can be set up from a parry8

The Codex even tells us to do this! It instructs us that if we turn away the opponent’s attack, we should drive in and attack them as soon as possible, and that delaying will be harmful to us (Fols 32v and 36v).

So what are we to do if the opponent applies this advice to us?

Unfortunately, the Codex doesn’t tell us directly. There is, however, a possibility that is hinted at in the text and I think lines up with the general principles.

On Fol 24r, there is a passage discussing the principle of turning our point towards the opponent’s face or chest after having won the Vorschlag. This is the passage in which we are told to position our point “half an ell” from the opponent. Towards the end of this section, there is a line that states: “Don't allow yourself to become relaxed or hesitant, nor defend too lazily, nor be willing to go too widely or too far around.”

Emphasis mine.

The context of this line is discussing a situation in which the Vorschlag has already been won (Chidester’s translation states that we have won the Vorschlag, Trosclair states that the opponent has, but regardless someone has) and we are engaged at the blade with our opponent. This line reminding us not to defend too lazily occurs in the middle of an engagement, not at its beginning.

How I would interpret this line is that it is a reminder that even in the midst of an exchange of blows, when we have delivered the Vorschlag and wish to follow with the Nachschlag instantly, we may still yet need to defend ourselves.

If you have delivered the Vorschlag, and your opponent immediately moves into the riposte, that riposte must be stopped or avoided before you can safely finish with the Nachschlag.

This is only my conjecture, to be clear. The Fol 24r text is fairly unclear and ambiguous on this point. Frustratingly the technique sections of the text don’t discuss this proposed “Attack-defend-attack” pattern in any clear way.

I do think, however, this reading is consistent with the general principles presented elsewhere in the Codex (i.e: Prudence, foresight, good reason, constant motion, never allowing the opponent to come to blows). It also allows us to integrate the techniques of Abwenden and Vorsetczen with our tactics of Vorschlag and Nachschlag. In my experience, this has made Vorschlag-Nachschlag tactics much more successful in my fencing.

I should clarify a point about this though: This interpretation calls for you, the KdF Fencer, to take the offensive always looking for the opportunity to finish with the Nachschlag. You fall back on strong defensive skills as a foundation of safety in the case an opponent defends successfully or attacks you first9.

What this interpretation does not call for is attacking into the opponent intending to draw out an anticipated riposte which you plan to counter. Those tactics may be successful and sound fencing in general terms, however I do not think they can be textually shown or evidenced in Ms3227a.10

With the use of opposition, and with diligent defending when the situation demands it, we have answers to the problems of counterattacks and parry-ripostes. We also see how Vorschlag and Nachschlag are not contrary to Schütczen, but are to be used in unison. We strive for both audacity and prudence together in our fencing.

To Vorschlag or to Vorsetzcen?

That is the question.

As I was composing this piece, I ran into a frustrating conceptual overlap between the Vorschlag and the Vorsetzcen within Ms3227a. Let me try to explain:

Within the Codex, the Vorschlag is the primary offensive tactic given. It can be conducted with either a thrust or a cut, and we have already discussed its characteristics.

The Vorsetzcen11 are a group of four actions the text gives. They are kinaesthetically related to or derived from the Hauen (Cuts), and we are told that they lead one into the Four Hengen (Hangers, Hangs, Hangings, however you translate it), from which one can perform Winden (Winds or Windings).

The text tells us that Vorsetzcen can deflect an opponent’s attacks defensively, can disrupt the opponent’s position or guard offensively, and we may also suspect some kind of preparatory function to them as (Depending on how you read the text that they “come onto the sword” of the opponent).

It is also stated that by going to the Hengen, we can “perform the art well” (Fol 23v), so evidently the Vorsetzcen are not the action or tactic of a poor or unskilful fencer.

So, I reasoned: Vorsetzcen come from cuts and can have an offensive function. Vorschlag can be delivered by a cut and is the main offensive tactic. It stands to reason that we could win the Vorschlag by using a Vorsetzcen.

Well, not quite. Corresponding with Maciej Talaga on the matter, he pointed out to me a critical and probably irreconcilable difference between these actions: Vorschlag aims only at the opponent, explicitly not at the sword. Vorsetzcen can in fact aim at the sword, as it must do so for its defensive function and the suspected preparatory function is also phrased in terms of going against the sword.

This turned out to unravel my proposed theory, which was rather frustrating! But I am glad that Maciej pointed this out to me as I had to reassess things more carefully and I think I came to a more accurate conclusion as a result.

The trouble was that there is an overlap in the Venn diagrams between the characteristics and uses of a Vorschlag and that of a Vorsetz. Principally this overlap exists in the offensive function. If the Vorsetzcen only served to deflect an opponent’s attacks, well then there would be no issue: You would Vorsetz when defending and Vorschlag when attacking and all would be well. Alas that is not how the text states matters.

Instead, we are told to take the offensive on the opponent via the Vorschlag, but we are also told that the Vorsetzcen will disrupt an opponent’s guard. Disrupting a guard appears to be an offensive function. The other overlap is that the Vorschlag can be delivered by a cut, and the Vorsetzcen bear some mechanical relationship to the cuts.

Furthering my confusion, the Codex also states that we counter all the guards by hewing boldly toward the opponent so they must defend, and that we shouldn’t be concerned with the guards but with winning the Vorschlag (Fol 32r). Does this then mean that the Vorschlag also disrupts guards just like the Vorsetzcen do?

So the question I came to: If the fundamental difference is whether we target the opening or the sword, when would I choose to Vorsetz in an offensive manner and when would I choose to Vorschlag?

Unfortunately, Ms3227a is not terribly clear on this point. There is a clear preference for targeting the opening rather than the sword. It would seem that the Vorschlag is the preferable offensive tactic. If, however, you can in fact disrupt a guard offensively with the Vorsetzcen, in what situations would you do that rather than take the Vorschlag?

I looked elsewhere within the Liechtenauer corpus of texts to see if other texts might give me some hint towards unravelling this mystery. I decided to compare Ms3227a with its closest KdF relatives, the Ringeck, Danzig, and Lew (RDL) glosses, on this matter.

In the RDL texts, there is a subtle difference on the subject of Vorsetzcen. In Ms3227a, the Vier Vorsetzcen are derived from the four basic cuts (That is, descending and ascending cuts on both sides). In RDL, the Vier Versetzen are four specific applications of the specialized cuts of the Liechtenauer tradition (Zwer, Krump, etc), used to attack specific guards of the opponent. Krump displaces Ochs, Zwer displaces Vom Tag, and so forth.

An interesting pattern emerged to me when I reconsidered the Vier Versetzen of the RDL texts while pondering this matter of Vorschlag vs Vorsetzcen.

In the Vier Versetzen of RDL, guards where the opponent’s blade is not extended forward with the point towards us are met with direct attacks towards the available opening. This attack may go to the opening while creating opposition, as in the case of using Zwerhaw to break Vom Tag. It also may not use opposition and simply strike directly, as in the case of Scheitelhaw breaking the position of Alber.

When the opponent’s blade is extended towards us then we attack directly while going into blade contact/opposition, as with using Schielhaw against Pflug; or, we strike into the blade to disrupt the opponent’s position while taking a strong position to attack from, as with breaking Ochs with Krump12.

Taking this pattern back to Ms3227a, I have this proposed interpretation then for the matter of Vorschlag or Vorsetzcen:

If the opponent’s blade is in your way, preventing you from safely taking the Vorschlag (Principally if it is extended forward with the point towards you in a threatening position, as in Pflug or Ochs), then use the Vorsetzcen and disrupt their guard with a cutting action, which may include striking their blade and positioning you advantageously for further action.

If, on the other hand, they stand with their blade refused (Held away, not within reach of you), either high as in Vom Tag, or low like Alber, then you take the Vorschlag by attacking directly towards an opening, using opposition for greater safety if required.

I would also propose that if the opponent is “not in guard”: Moving without settling into a ready position, making uncommitted or unthreatening motions, or anything else, then you should also take the Vorschlag promptly and directly.

Here my opponent is moving with unthreatening cuts out of distance, not settling into any guard or position. I drive in with the point directly to the opening.

In all cases, observe the general rules of moderation and measure in all your fencing. Be brave and audacious, but balanced with prudence, observation, and good sense.

To be clear, this is only my proposal. This is my conjecture working within incomplete evidence. Ms3227a is not, unfortunately, very clear on the different use cases of Vorschlag and Vorsetzcen in offensive fencing. The RDL texts are a useful point of comparison and source of “frog DNA” for understanding 3227a, but they differ from 3227a in various ways that mean that citing them is not necessarily authoritative on an interpretation of the Codex.

That being said, this is I think the most coherent hypothesis I have yet come to on this particular matter. I believe it is consistent with the rest of the 3227a text and creates reasonably clear tactical use cases between Vorschlag and Vorsetzcen.

Remarks on training

This has been a very long piece, and it is time to bring it to some conclusion. First, however, I would like to make a few brief comments on how I have been training to use the Vorschlag and Nachschlag, with the hope that you, reader, may also be able to use some of these things in your training:

On an individual level, I work at home on the pell and on the air on throwing the Vorschlag and Nachschlag together in one flow. I try not to throw one attack at a time, but move through one then the next seamlessly. I also will practice making a Vorschlag, an immediate parry, and then a Nachschlag, also all in one flow. When practicing the Nachschlag, I focus on making short and direct follow-up attacks from the Vorschlag, trying to avoid the wide side to side motions which the Codex condemns and which are often too vulnerable to a riposte.

Exercises with training partners need to focus on:

Closing distance and threatening effectively with a confident direct attack

Working off a parry into an immediate Nachschlag by the shortest path.

Recovering and defending an opponent’s ripostes when they successfully throw it faster than your Nachschlag. Slices against the wrists at close distance, blade parries or beating sweeps at longer distance.

Attacking with opposition against a direct counter, as in Zwer and Schiel.

Prudence and observation of an opponent’s habits and behaviours. Choosing appropriately when to Vorschlag and when not to, when to use the Vorsetzcen and when not to, and when to defend instead.

Decision-making using Fuhlen at the blades. Driving in directly against weak pressure, targeting a new opening against strong offsetting pressure.

Generating surprise in the attack

Entering the engagement with a coherent and preconceived plan of action.

The footwork, positioning, and body mechanics which enable all of these tactics to succeed.

Cooperative training one on one with a coach is always good, but many of these skills can also be beneficially practiced through competitive sparring games. In particular, I find attacker-defender games such as sabre march are very helpful.

In cooperative training, I focus on generating ideas and concepts to take into competitive environments. In competitive training, I focus on learning how to execute these ideas under pressure.

In freeplay, I try to pick one particular aspect of these tactics and focus on it as consistently as possible. For example: I may choose to focus an entire bout on winning the Vorschlag with a direct thrust. If my opponent is defeating me when I do this, I try not to abandon my intended focus to win the sparring but instead to persist. From this, I try to understand:

What conditions enable a particular aspect or approach to Vorschlag and Nachschlag to succeed?

What conditions cause me to fail with these tactics? What can my opponent do to foil me?

How can I force the conditions of success? How can I foil the opponent’s conditions of success?

Conclusions

The Vorschlag and the Nachschlag are arguably the central tactic within the fencing teachings of the Nuremberg Codex. Understanding them then is a critical aspect of understanding and applying this source’s teachings. It also forms a unique and distinctive aspect of this source in comparison to other sources of the Liechtenauer tradition.

A simplistic read of the source may suggest that the Vorschlag and Nachschlag is nothing more than an aggressive, all-out attack, relying only on an opponent’s defensiveness to keep yourself safe. I think this read is shallow.

It is superficially true that the source recommends we keep up the offensive and keep the opponent defending, however this needs to be read and understood in the context of the rest of the source, which reveals a more nuanced and complex approach.

It is my belief that Vorschlag and Nachschlag are to be applied in a manner consistent with the overall fundamentals that the text provides for us. This includes prudence, deliberation, and wisdom as much as it includes speed and audacity. Measure and moderation are to be observed in all things we do in fencing. Schütczen, defences, are given as a fundamental alongside cuts and thrusts.

The Vorschlag and Nachschlag should not be a mindless, overly aggressive attack at all costs, but a well-conceived attack to take the initiative intelligently. This attack should be delivered with speed and surprise, along the most direct path, and supported by a complete and coherent plan.

It should also be a measured and controlled attack, not committing so hard or so foolishly that we expose ourselves rashly to stop-thrusts or parry-ripostes. At the conclusion of the Vorschlag, we should be composed and collected for an immediate Nachschlag, or to meet the opponent’s riposte with a defence if required.

We should strive to keep the opponent defending if possible, but if they do manage to launch attacks we should be ready to defend ourselves by taking a parry, slicing across their wrists, or otherwise avoiding or stopping their strike.

If the opponent’s guard offers an unavoidable obstacle to our taking the Vorschlag, then we may instead choose to use the Vorsetzcen and break or displace their guard first before proceeding to our strikes.

This concludes part 1 of this series. Part 2 will follow, with a more in-depth treatment of the texts from which I drew and interpreted the ideas outlined above.

I hope this piece was of interest to you, and perhaps you learned something or reconsidered these ideas in a new light. If anything here appears incorrect or mistaken to you, do let me know in the comments or by message! I would be delighted to hear of contrary views and learn from my fellow students of the Art.

Credit to Martin Fabian for the clip. Longsword! Part I - The Best Nachschlag

Armizare in Paris: Revisiting the Punta Crossing

Martin Fabian: Tyrnhaw 2019 - Longsword Men - My fights

As in, fencing as if you believe yourself to be the main character of a movie or video game, able to act with impunity while your opponent will haplessly freeze up and do nothing to stop you.

Wiktenauer: Pseudo-Hans Dobringer

Anton Kohutovič: Longsword.academy: Fühlen-less schielhau concept

The Late Counterattack, for further discussion.

The second clip comes from my own footage. The first is from Akademia Szermierzy: Countering the Direct Attack

This approach bears some similarities to the works of Zbigniew Czajkowski. Consider the following passage:

“Although it may sound paradoxical, the technical and psychological basis of an offensive style of fencing is confidence in defense.

Confidence in defense allows the competitor to maneuver freely on the strip, to push the opponent to the end line of the piste and to prepare attacks comparatively calmly and with assurance.

A fencer with strong offensive drive who is preparing and concentrated on his attack, may suddenly be attacked by his opponent. Such an unexpected attack forces the attacked fencer to rapidly switch his/her thoughts and attention to avoid being hit.

A fencer who has an excellent command of parries and counter-attacks may allow himself/herself to come almost dangerously close to the opponent to launch an attack at the appropriate moment.”

As an aside on this point: I don’t think you can base an interpretation of Ms3227a’s fencing on actions which involve allowing your opponent free, uncontested opportunities to strike. The 3227a fencer should have good defensive skills as a foundation for those situations when the opponent does strike at us against our will, which of course will always happen, but there is a difference between that and allowing the opponent to strike so that we can counter or parry-riposte.

If I had to speculate, I don’t think the Codex wants to give the Opponent any chance to succeed if it can be avoided, and tactics in which you wait upon a parry or a counter opportunity gives the opponent freedom to strike as they will, which always means a greater risk that they succeed and hit you.

Could be variously translated as “Four Parries, Four Displacements, Four Forward Placements, Four Forward Positions, etc”. See Talaga, On Hengen, Winden, and other things, for further discussion.

This is admittedly a contentious interpretation of Krump against Ochs, but that’s a topic for another article.