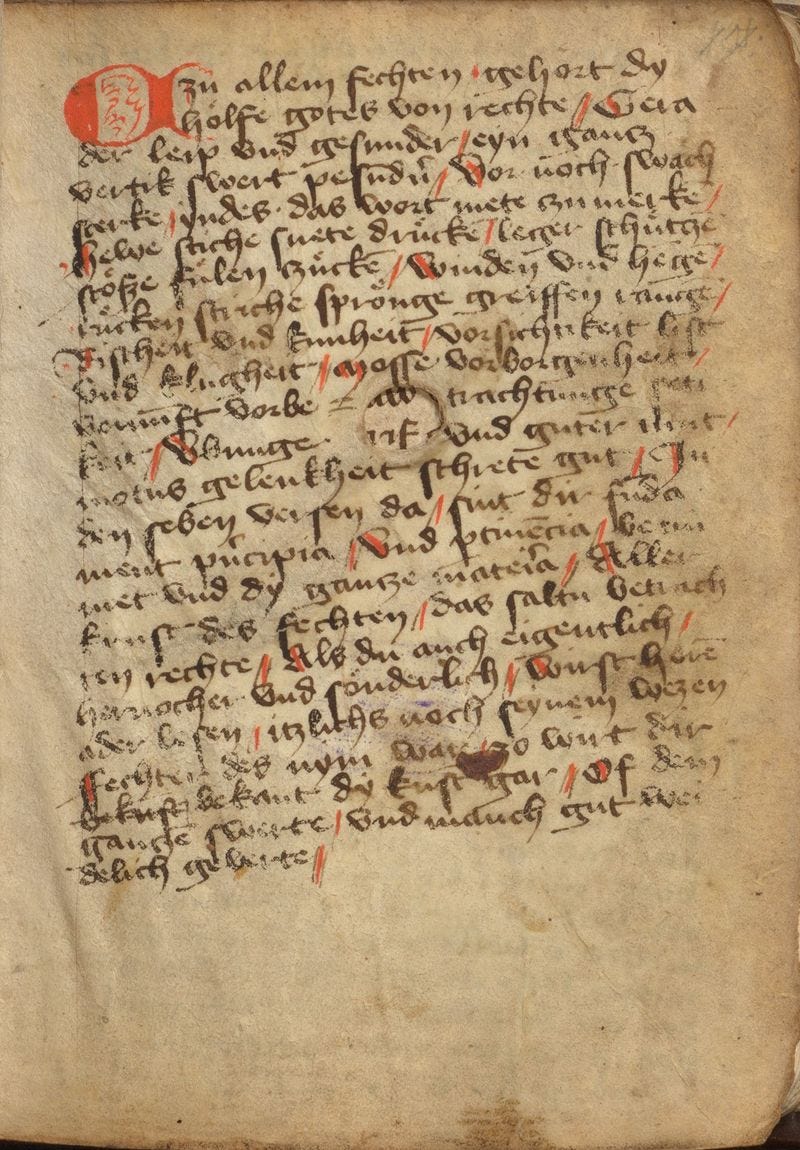

Manuscript 3227a is my primary source from which I study Liechtenauer’s Kunst des Fechtens. It has many unique characteristics as compared to the Ringeck, Danzig, or Lew manuscripts which are perhaps the more usual foundation for the modern KdF student. It has a unique set of teachings and advice which are only found in 3227a and not in the “RDL” group of texts. One of these unique pieces is a section of verse on Folio 17r, which begins with the phrase: “Oh all fencing requires…”.

The passage goes on to list what it describes as “fundament principia und pertinencia”: Fundamental principles and concerns of fencing. The verse seems to describe what the author regarded as the basic characteristics that one required to be successful in fencing.

This is very interesting! HEMA texts often fixate on techniques and tactics, and leave basic foundations unspoken or implicit. A list of what foundations this author at least regarded as essential is potentially a very useful tool for the modern HEMA student. Additionally, this verse is unique to Ms3227a and not repeated in the RDL corpus, and that makes it a matter of interest for the students of 3227a.

Unfortunately for us, this piece of text is a verse: It describes the matters briefly, in rhyming couplets. This was perhaps a memory aide, or maybe this list was just notes from the author on the requirements of fencing. It does not go into detail explaining what it means with the words it uses.

My intention in this piece is to examine the 17r verse from 3227a. I’m going to use the method of the KdF manuscripts themselves: I will be glossing this verse. That is, I will be writing my own prose explanation of what the lines of this verse means. I will be using my own experience in fencing and HEMA competition to offer a potential model for what these “principia und pertinencia” are and what they may mean for the modern HEMA fencer studying this text. I will also use references to other texts, other pieces of historical or fencing context, or the work of other modern practitioners where necessary to try to enrich or deepen the gloss I offer.

Bear in mind of course that my gloss here is only one of many potential ways of understanding this text. I am not the final word or the final authority by any means, merely one humble fencer offering my thoughts. If you think I am wrong or mistaken in any place, I would love to hear of it and discuss it further!

Throughout this gloss, I will be using the German original and the Michael Chidester 2022 translation, sourced from Wiktenauer1.

Let us begin then:

Original: CZu allem fechten ·

gehört dy hölfe gotes von rechte /

Gera der leip vnd gesvnder /

eyn gancz vertik swert pesundern /

Translation: OH, all fencing requires

The help of the God of Righteousness,

A straight and healthy body,

And a complete and well-made sword.

Gloss: Being a product of the latter Middle Ages, Ms3227a of course emerged from a much more religious society than our modern times generally are. It is fairly typical for such a text to begin with an invocation for the help of God. You might compare the line about God in this verse to the opening of Liechtenauer’s Zettel, which states “Young knight learn onward/ For God have love”.

Debates about religious belief are outside the purview of this blog and this article, but what might it mean that fencing requires the help of God? I think that part of this line is an acknowledgement of the role of luck, chance, or perhaps of fate, in the outcomes of sword combat. You may be trained and prepared as best you can be, and still lose if luck does not go your way. If you are going to embark on combat with the sword, it is best to know that God or “God” (i.e: The universal vagaries of fate and chance) has a great influence on determining the victor, and we should be at peace with that.

The other part of this line is that it specifies that we need the help of the God of Righteousness. If we look elsewhere within Ms3227a, in particular to the “Other Masters” verse on folio 27v, it states: “you should not learn fencing / To overpower someone with your art / for unjust reasons”2. I think that the invocation of the God of Righteousness suggests that we should embark on fencing only for good reasons or a righteous cause. In our modern practice, I think this means fencing for the many good things it can bring us: The joy of movement, the pleasures of friendship and camaraderie, the honing and sharpening of our strength and wits and courage. We should not fence in anger, nor to harm others, nor out of fear or insecurity in our egos.

To quote Master Yoda: “Anger, fear, aggression; the dark side of the Force are they.”

There is also a practical aspect here: Combat in earnest, and yes combat in sport as well, is strongly psychologically demanding3. Willpower and belief can matter just as much as skill and physicality. A sense of moral rectitude, a sense of righteousness in your cause and conduct, is a powerful aide to the psyche of the individual in combat.

It is interesting to me that the very second item listed in the verse, right after the help of God Himself, is that we need a healthy body. In the late medieval period, people of all walks of life generally lived much more physical lives than the more sedentary modern person does. However, they had less in the way of medical knowledge and technology than we do today. A person with physical limitations has more ability now to engage in physical pursuits than perhaps they did in the 14th or 15th centuries. For instance, see the sport of wheelchair fencing. Even so, your physical fitness remains the top asset of any fencer, whether you are fully able-bodied or you live with a physical limitation of some kind.

Although fencing skill can allow the weaker person to overcome the stronger one, it remains true regardless that physicality is an enormous asset. It is an asset we as fencers should cultivate just as earnestly as we cultivate skill in fencing. What, after all, is a sword without the hand? Without the arm? Without the body? Just a length of metal, nothing more.

Of course that brings me to the final item in this section, “a complete and well-made sword”. The Kunst des Fechtens of Liechtenauer is a weapon art, and we need a weapon with which to use it. Thankfully, another portion of the text lists all the parts which are required for a sword in this art: “The point, both edges, the hilt and pommel”. This sword must also be well-made. KdF makes heavy use of blade to blade actions: Binding blade to blade, winding, and so forth. We need a sword that is going to withstand the strains of this use, and not fail us or fall apart or break in the moment we need it.

Original: Vor · noch · swach sterke /

yndes · das wort mete czu merken /

Translation: Before, After, Strong, Weak;

'Within', remember that word;

Gloss: The Five Words of Liechtenauer’s KdF have been discussed quite extensively across the HEMA world. Much digital ink (and sometimes blood) has been spilled in particular over that sharp word “Indes” and what it might mean. I will not be reiterating those arguments today, I will instead merely briefly summarize my own thoughts and interpretations of the Five Words for the sake of completeness before we move on to other verses:

Vor, Before: The leading actions which open an engagement. In particular in 3227a, this refers to the Vorschlag, or Leading Strike, which shapes the subsequent pattern and development of the engagement by demanding a response from our opponent.

Nach, After: The following actions which shape an engagement after it has begun. The best example of this is the Nachschlag, the Following Strike, which we may throw after we have made a Vorschlag, or which our opponent may throw as well.

Swach, Weak: The portion of the blade from the middle to the point, with which we have less leverage for blocking an opponent’s strikes or manipulating their blade, but more reach and acceleration for striking at them. This also means understanding when you or your opponent are weak or lack leverage in a bind of blades.

Sterke, Strong: The blade from the middle to the cross, which is more rigid and has greater leverage and is thus more advantageous to use when defending ourselves or manipulating the opponent’s blade. As well, understanding when you or your opponent are strong or have advantageous leverage in the bind.

Indes, Within: Reading effectively the pressures and tactile sensations of a blade to blade meeting, to make effective decisions within the engagement on what next action to take. Used correctly, this often results in the fencer striking their opponent in between one action and the next.

Duplieren is an example of an action done in an “Indesly” fashion. Credit to Martin Fabian for the clip4

Original: Hewe stiche snete drücken /

leger schütczen stöße fülen czücken /

Winden vnd hengen /

rücken striche sprönge greiffen rangen /

Translation: Cuts, thrusts, slices, pressing,

Guards, covers, pushing, feeling, drawing back,

Winding and hanging,

Moving in and out, leaping, grabbing, wrestling,

Gloss: The verse now lists a series of physical actions involved in fencing, beginning with the “Drei Wunder” of cuts, thrusts, and slices. I believe that listing these physical actions here among the principles of combat is meant to tell us that we must be competent in all the basic mechanical aspects of fencing with the longsword.

Other texts in the KdF corpus refer to the “Drei Wunder” (Three Wounders, or perhaps Three Wonders) as the three fundamental ways with which you can use your blade to strike or wound your adversary. I will not say much of them, as others have spoken of them extensively, but I will say that all of these require constant practice and honing

Following those with “pressing” as one of the fundamental actions is interesting. It may be listed that way merely for the sake of the rhythm of the verse, but pressing into the opponent with your blade has a value of its own which I think merits consideration. Within this list, a fencer could order these attacks in terms of the distances involved: One can strike with the thrust at the longest reach, the cut at middle distance, and the slice in closer distance. At closer distance still, at corps-à-corps, slicing into the opponent’s wrists or hands and then driving and pressing into them is a good way of physically controlling the opponent and limiting their ability to act with their blade.5 Experience has shown me that you can achieve this simply by pressing or shoving the opponent’s arms with your own, even without blade contact.

After this comes “leger schütczen”, which Chidester has translated as “Guards, covers”. Later in the text, the 3227a author will state that there is little to be held about guards or positions, namely that you should not wait too long in them. Yet it also takes the trouble of describing the Four Guards of KdF, albeit briefly, and it also lists guards here among the principles. Why are guards important then? I think because first of all your own starting position influences what actions and tactics will work best for you if you engage from said position, and secondly the opponent’s position influences the same for them. Understanding your position and theirs and what actions can come from either most naturally or most effectively offers you a lot of information about what kind of engagement is about to occur, before either fencer has thrown a blow.

“Schütczen”, or covers. The word can also be used in German to refer to defending, protecting, or safeguarding something. This refers I believe to the importance of defensive actions in the art of fencing. Kunst des Fechtens is often stereotyped as a very offensive-heavy approach to fencing. I think controlling the engagement through being proactive and offensive is indeed the goal, but one shouldn’t do this heedless of the opponent’s threats or strikes, and so defensive actions such as parries, beats, and sweeps are also essential.

To parry is as fundamental as to strike

I believe that “pushing, feeling, drawing back,” all refer to actions taken from blade contact. I had to wrack my brain trying to figure out how the “Pushing” in this bit might be distinct from the pressing listed above or grabbing and wrestling listed below. My current interpretation is that these three items are all things that one does when blades have bound together. The word “Feeling”, fülen, is what leads me to think so. “Feeling” throughout KdF texts is what occurs when you are in blade to blade contact and you have tactile feedback on the opponent’s weapon, with which to read its position and determine your next action. If my interpretation is correct, then “pushing” would refer to pushing into or striking through the bind, such as when one thrusts the opponent with blade contact as in Zorn-ort or other plays. “Drawing back”, czücken as 3227a gives it, would refer to pulling away from or disengaging from the bind.

One possible piece of evidence supporting this read is the Codex’s later instructions about tactics following a Vorschlag and meeting the opponent’s blade. If the opponent is Strong and Hard in the bind, we are to become Weak and Soft, letting them push the blade aside and drawing our sword back, and then strike to the next closest opening created by the opponent pressing on our sword. If the opponent is Soft and Weak in the bind, we are to be Strong and Hard and push in and drive with the point at their face or chest, or otherwise strike them however we can. In other words, after a Vorschlag we can use “pushing, feeling, drawing back,”.

Winden vnd hengen, Winding and Hanging, I think are further actions taken within the context of a blade to blade engagement. To paraphrase Maciej Talaga’s work on Winden and Hengen6, the Winden are performed from the Hengen, which come from Vorsetczen, which themselves come from the Hauen. I understand it like this: The Hangs of the sword are the positions in which we arrive after we have entered the engagement by striking at the opponent. Preferably this should be a position of advantage, where we are safe from a direct attack from the opponent and we can ourselves strike at our opponent. From the Hanging, we drive Winds, which are movements of the blade. I believe that the Winds are the manoeuvres of our blade, within the context of an engagement from the initial blade to blade contact, in which we either fend off the opponent’s strikes or position ourselves to deliver our own strikes, or both if necessary.

One allegation often made about the KdF texts is that they lack instruction in footwork. There is some justice in this, in that KdF texts do rarely address footwork. It’s noteworthy then that in the list of principles, we see the item “Moving in and out”. This refers I think to footwork, specifically both being able to smoothly and swiftly advance or retreat, and knowing when it is best to do so. It could also refer to moving into engagement with the opponent, and moving out of an engagement. In 3227a’s general fencing advice7, one of the few remarks it makes about footwork is a repeated comment that our footwork should be able to move forward and backward as needed, and I think that “Moving in and out” is referring to the same idea.

“Sprönge”, or Leaping (Could also be translated as “jumping” or “springing”), also implies a footwork item. In this case, the word implies rapid, explosive movement. Throughout the rest of the Codex, we will be told often that springing or leaping is a potential option for footwork, something listed differently than merely stepping, by which we can reach our opponent or drive into wrestle. I believe this item is telling us of the fundamental importance of explosive movement, especially explosiveness of the legs.

Finally, “grabbing, wrestling”. These refer to the grappling actions we may make use of in a sword combat, sometimes called in other texts “ringen am schwert”, wrestling at the sword. Grabbing I think means our initial grasp or laying of hands onto our adversary, while wrestling I believe refers to how we proceed from that initial grab to subdue our opponent, whether by manipulating them to open them up for a strike with our sword or by throwing them or disarming them of their sword or any other thing.

Original: Rischeit vnd kunheit /

vorsichtikeit list vnd klugheit /

Masse vörborgenheit /

vernunft vorbetrachtunge fetikeit /

Translation: Speed and audacity,

Prudence, cunning and ingenuity,

Moderation, stealth,

Reason, deliberation, readiness,

Gloss: Having listed the basic mechanical actions necessary for the art, the text now moves on to for four lines listing skills and attributes which fall more on the mental side of fencing than on the mechanical. These are internal characteristics to the fencer’s mind and spirit, or they are tactical principles, not necessarily mechanical actions.

The first, speed, is a peculiar one to find in what is otherwise a section given over to the mental. The German “Rischeit” seems to be a form of the more modern “Rasch”, which is used as an adjective meaning “Rapid” or “Quick” or “Swift”. Rascheit could be rendered as “Rapidity” or “Quickness”. Chidester uses “speed” as his translation, while Jens P. Kleinau’s work prefers “celerity”8, but the dominant impression of the word in any case is about quickness.

This could refer simply to physical speed, the rapidity of your execution of movements. Physical speed is a great asset in fencing! But I think that its position here in the lines that talk about mental and emotional states instead point to a more mental-oriented reading of the word. I think that the speed meant here is more about speed of thought, not speed of action per se. Being quick in perception and observation, quick in judgment, quick in planning, quick in decision. It has often been my experience in longsword fencing that being able to think and judge quickly is often more significant for success than your physical speed alone. A very fast fencer who dithers and hesitates may be unable to use their speed against the slower fencer who acts first and decisively.

Kunheit is translated here as “Audacity”. Bravery, daring, fearlessness, or boldness might also be appropriate words.

Fencing by its nature is a matter of taking risks. Whether for sport or for serious combat, either which way there is always an inherent risk. The risks are many and multiple. In fencing, there is always the risk of defeat and loss. This could be only a risk to your ego, but it could mean a loss of face, a risk of shame or personal disappointment. It could also be a risk to your body. There is always a risk of injury, and potentially serious injury. Our modern fencing game is much safer than the fencing sports of the 15th or 16th centuries, and of course immeasurably safer than to fence with sharp blades in anger, but it still has its injury risks as a combat sport. To embark on fencing then is to embark on a risky enterprise. A measured disregard for risks is what is needed. One must have a cool, collected, conscious fearlessness of fencing’s dangers.

But, there is balance in all things. Audacity alone cannot make a good fencer. One also must be prudent. The word vorsichtikeit can also be translated as “caution” or “carefulness”, but I think “prudence” is best. Being fearless of dangers doesn’t mean one should rush headlong into them. A mountain climber embarking on a difficult ascent does not do so carelessly, unequipped and unprepared. The climber is trained, he carries specialist equipment and clothing, he plans his approaches carefully, he considers contingencies for emergencies, he ensures he has adequate supplies and water. So too the fencer should be prudent. I think prudence means a healthy appreciation for the risks and dangers inherent in fencing, preparing for them in your training, and planning to deal with them in your approach to your opponent.

How do we deal with the dangers of fencing? That brings us to our next items, cunning and ingenuity. In my experience, fencing cannot be learned or practised by rote. Set techniques or preconceived tactics can be useful as learning tools; however, live fencing against a resisting active opponent is unpredictable, and often requires a more improvisational approach. If you find your opponent well prepared or strong against your preferred tactics, you may need to abandon them and try something different to win. This is where cunning and ingenuity is critical, being able to flexibly come up with clever new solutions to the problems your opponent presents.

Cunning I believe also refers to the importance of deception in combat, inducing your opponent to lower their defences, leading them on, outmanoeuvring them, and laying traps for them in your fencing.

Here I offer my blade to the opponent, seeming to threaten with the point, and I disengage to strike the hand.

Masse, moderation. Here I will be so gauche as to quote my own previous writings in another article: “The German word, Maße in modern German, seems to carry implications both about the measuring of a physical object or area, and implications about measure as in having moderation or self-control. Linguistically, the mosse in the Codex more probably means moderation and self-control, but both implications are appropriate for fencing.”9

This unassuming little word is at the heart of many of the lessons that 3227a repeats throughout its longsword text. We are told that one of Liechtenauer’s sayings is that “all things have measure and moderation”, and that this applies to our strikes, our stepping, and all plays and pieces in fencing10. This means that we should be balanced in our approach to fencing, maintaining moderation in everything and avoiding undesirable extremes: Audacious but not reckless, prudent but not fearful, strong but not relying on strength alone, and so forth. Don’t step too far or too short, don’t attack too aggressively but do not hesitate and fail to attack. This idea of having balance between opposite undesirable extremes is a very medieval piece of philosophy, one can find similar ideas expressed in Geoffroi de Charny’s Book of Chivalry11 for example.

The other thing about this idea of measure and moderation is that maintaining our balance is a dynamic thing. Like the codex’s description of footwork as “standing on a set of scales”, maintaining our balance in our fencing means constant adjusting and change: Now becoming more aggressive when aggression is merited, now being more cautious where prudence is necessary.

Vörborgenheit, translated by Chidester as “stealth” is another peculiar idea to consider as applied to fencing. It becomes more clear when we consider some other translations of this word, such as “concealment”. This means endeavouring to conceal from our opponent what our intentions are or will be. We don’t want to telegraph or project what we intend to do such that the opponent can foil it with a well-conceived and prepared plan of action, we want to create surprise when we act. Consider this while remembering another line from the codex: “Whatever you want to perform cleverly, in earnest or in play, should be hidden from the eyes of your opponent so that they don't know what you intend to do to them.”12

These four lines conclude with “Reason, deliberation, readiness”. The idea communicated here is the importance of judgment and consideration in our fencing. To be successful, we need to be able to observe our opponent, observe their actions and habits and behaviours, and consider well how to best approach and defeat them. At the same time, it is no good to get so lost in consideration that you hesitate or fail to act, and I have often been hit in my bouts when I am deeply thinking about what to do and my opponent acts simply and hits me. Hence the importance of also being constantly ready for action, ready to commit or to change your plans and act on the fly if necessary. The takeaway from these principles are best summarized by the Codex itself: “Do not be hasty, consider well in advance what you want to do, and then do it boldly and swiftly”13

Original: Vbunge vnd guter mut /

motus gelenkheit schrete gut

Translation: Exercise and good spirit,

Motion, dexterity, good steps.

Gloss: “Ubunge”, exercise. Put another way: Practice. Practice, practice, practice. One of the Codex’s most remarked upon passages states “Practice is better than artfulness, because practice could be sufficient without artfulness, but artfulness is never sufficient without practice.” We may have all the skills and attributes of the good, artful fencer, but in order to succeed against skillful, resolute opponents, we must practice and hone our abilities.

A friend of mine has a saying about martial arts: “The brain is smart, the body is stupid”. It’s very much true in fencing. I have often been fencing, seen a possible opportunity and thought to myself “I could defeat this opponent by simply using this technique”, and then my body was unable to put it into effect. That is the outcome of not enough training, or training which is not developing the right skills. Even if you are a fencing champion in your own mind, it matters little if you can’t make the right tactics and techniques happen at the right time with your body, and that requires practice.

Good spirit. I mentioned earlier the psychological rigours of combat. These are present even in the fairly friendly and low-stakes environment of HEMA’s sport competitions, and any cursory study of military history will attest to the enormous influence of the mind and the emotional state of humans on the outcomes of battles. Nervousness or fear of an opponent can defeat you before you even begin to fight.

I have experienced this from both sides in my competitive experience. I can remember many bouts I have had where I could have done more to contest the result, but stress, nervousness, or being intimidated by particular opponents undermined my ability to perform. I have also had bouts where I became angry or frustrated that I was losing, and became overly aggressive, which of course only made me easier for the opponent to defeat. On the other side, I have also gone out to fence only to observe that my opponent is paralyzed by nervousness, or intimidated by myself, or is angry that they’re losing and starts making stupid mistakes. With such opponents, it’s quite easy to win.

I interpret “good spirit” in line with the Codex’s other teachings on moderation and reason. It should be a cool and level head, with a calm and collected determination to win, and the self-confidence that you can prevail. You should be neither too high spirited (Arrogant, angry, aggressive, jumpy, etc), nor too lowly spirited (Nervous, fearful, fixated on defeat), but strive to maintain a balanced and collected frame of mind.

It is interesting to me that “exercise” and “good spirit” come together on the same line, because the best way to develop the fencer’s confidence is through training.

In the final lines of this verse, we return to the physical aspect with “Motion, dexterity, good steps”. A later line of the verse on Fol. 17v will tell us “Motion', that beautiful word / Is the heart and crown of fencing”. Fencing is an art of movement, the movements of the body through which we move our sword.

Good steps I think plainly refers to effective footwork: Agile, balanced, navigating the distance required in the correct timeframe, adaptable, and providing the necessary positioning and footing for our tactical plan of action.

What then is dexterity in this context? The word “gelenkheit” seems to come from “gelenk”, which refers to a joint. A literal translation might be something like “jointness” or “jointedness”. Trosclair gives it as “flexibility” and Stoeppler translated it as “agility”. I will maintain Chidester’s version here and think about it as “dexterity'“.

It could mean dexterity in motion generally, or being dexterous with our good steps. However, my general assumption throughout this gloss has been that each word listed in the verse refers to a different, distinct idea worth considering on its own14, and so I don’t think dexterity is a redundant term here. I think rather that it refers to what later Joachim Meyer would call handwork: The movement of our blade with our hands. I interpret this to mean dexterity in our blade actions, in the use of our hands, arms, and body to smoothly, nimbly, strongly, and effectively wield the sword.

The verse of the principles concludes with this line. For all the many and varied technical and mental fundamentals found within the art of fencing, it ultimately all comes down to motion, the heart and crown of fencing. It’s an elegant summation, in my view.

In these several verses

Are fundamentals, principles

And concerns,

And the entire matter

Of all the art of fencing is labelled for you.

Conclusions:

This small project glossing a verse of Ms3227a has been enlightening to me in many ways.

First of all, this piece has experientially demonstrated to me what a considerable undertaking it must have been for the glossators of Liechtenauer’s Zettel to produce their texts. Knowing but a little about the art of fencing (A very little in my case!), it is clear that in a didactic verse such as this one, each particular word can be extremely rich with meaning. In my case, I also laboured under my very rudimentary grasp of German (Aided by Google and Wiktionary and many good friends in the HEMA community). I had to weight not only what the translator had given, but also alternative translations, and what different implications could mean about the message to the fencer. 5,000 words of interpretation later, I feel I have a little of a better understanding of what the glossators had to go through to unravel Liechtenauer’s Verse in prose form!

Secondly, producing this gloss has helped clarify my thoughts about what are the true essentials and basic foundations of longsword fencing. Is my understanding of these matters identical to that of the 3227a Author? Likely not, although there is no way to know for sure. However, Ms3227a gave me a structure and a scaffold through which to think upon and consider these matters. Looking at this verse and trying to explain its meaning to the fencer helped me think about and better define the fundamentals of fencing for my own understanding. In this way, this project I think sheds a little light on a potential reason why the gloss authors may have produced their texts for themselves, as well as equipped me with a better understanding I can use as a fencer and an instructor today.

For myself as a fencer, thinking on the fundamentals in this way has helped me see where my current areas of strength are, as well as things I still do not fully understand or in which I need further improvement. I have some notions on how I can further improve my training to better grasp the fundamentals and apply them more effectively. I hope also to use this to guide my instruction and coaching of others.

I hope this piece has been interesting or helpful to you as well, reader! And if you find anything I have written incorrect or you think I am wrong, please let me know as well so we can discuss the matter further and better both our understanding. But now I think I will leave this here and go seek out some practice for my art!

See Johan Harmenberg’s Epee 2.6, pgs 72-74 and 159-162 for comments on psychological pressures and their influences on fencing.

Much Ado About Slicing, for further discussion of slices and presses.

Fol 15v and 64v.

Fol 22v.

De Charny: “You should plan your enterprises cautiously and you should carry them out boldly. Therefore the said men of worth tell you that no one should fall into despair from cowardice nor be too confident from great daring, for falling into too great despair can make a man lose his position and his honor, and trusting too much in his daring can make a man lose his life foolishly”. A Knight’s Own Book of Chivalry, Kaueper & Kennedy, 2011, pg. 70-71.

Fol 15v.

Fol 64v.

This assumption could be mistaken of course, but it’s my operating assumption for the moment.

Great write-up, Eric!

One minor comment I'd have is about your take on "gelenkheit" as manual dexterity, or skill in handwork/bladework.

It is true that "gelenk" means "joint", but "gelenkheit" may also be a medieval spelling of modern "Gelegenheit", which translates as "opportunity, chance". Located as it is in the Codex it would make sense this way, as it follows "motus" and precedes "schrete gut" - motion can logically be taken to mean taking opportunities through good footwork.

But there is another way to interpret it. "Gelenkheit" is historically-attested to denote "Gelenkigkeit", at least for the 18th century, but quite possibly also earlier. The "Gelenkigkeit", in turn, is defined as "joint articulation" and refers to the individual's range of motion in the joints*. So I'd say that Trosclair's rendition of it as "flexibility" is likely the closest one.

* See, for instance, here:

- Gelenkheit as Gelenkigheit: https://www.duden.de/rechtschreibung/Gelenkheit

- German Wikipedia on Gelenkigheit: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gelenkigkeit