Content note: This article uses some images from HEMA sources featuring sword wounds. Being medieval and Renaissance art for the most part these aren’t too graphic, but still some blood and wounding is portrayed. Let the reader use their discretion.

Here is a scenario which I think many people have encountered:

You are fencing an opponent, perhaps in club sparring, perhaps in a local tourney, maybe visiting another club for a sparring day. You are moving back and forth, trying to set up an attack. Finally your preparation succeeds and you launch your attack, perhaps it is a dominant side cut on an explosive pass. You execute well and your cut goes hurtling towards the opponent’s head. You anticipate a clean hit as the opponent isn’t parrying in time.

Then at the last possible second, split moments before they get hit, they suddenly lash out and hit your body or your leg or some other part of you which isn’t covered by your incoming sword. There isn’t possibly time for you to perceive or address this sudden threat. You finish the attack and hit their head, they land their hit to your body, and yet another HEMA double has happened.

This, my friends, is what I call the late counterattack. It maybe coincidentally resembles the proper counterattack in that it is, roughly, an attack delivered into an incoming attack, but there the resemblance ceases. The important word here is late, this type of counterattack is identified primarily by the lateness of its timing, which is what makes it very hard to either predict or to deal with as the attacker.

Let’s discuss the late counterattack, what it is and how it works. I hope to demonstrate to you why this habit is so extremely corrosive to the development of good fencing in your club, and hopefully I will persuade you to address the topic to your students and your clubs. I hope that if people understand why late counterattacks are bad and undesirable for their fencing objectives, we can take more effective steps to teach students to fence with better means.

First Principles

Let us begin by breaking this down to very fundamental, basic levels.

Every attack with a weapon (or indeed with your fist or foot) must cross space, or distance as we usually say in fencing, to reach its target. This takes time. The longer the distance, the longer the time, and vice versa. Every movement of the weapon from one point to another, be it a parry or a shift in position or a preparation to attack or anything else, likewise also crosses space and takes time.

The timeframe it takes for the weapon to move from point A to point B is often called “tempo” in fencing. But because “tempo” is an overused and much abused word that gets conflated with many other meanings and connotations, and because it is a specific word to certain HEMA traditions and sources and not to others, I will instead use the more neutral “timeframe” or “window of time” to refer to what I specifically mean for this article: How long it takes the weapon to move from where it is to where it is going.

When a fencer attacks targeting your head or body or any other part of you, there is a timeframe it will take from the moment they launch their attack to the moment it lands. If the opponent has judged their distance and executed their attack correctly, then at the end of that timeframe you will be hit.

That timeframe is how long you have to enact a defence before you get hit. It’s the countdown to the hit you are about to receive, in essence. There are many things possible to do within that timeframe: Attempt a parry, attempt a retreat or a side step, combine a parry with footwork, or perhaps attempt a counterattack.

A counterattack is when in response to that incoming attack, you attack into it yourself. There are many ways to do this and many authors call the successful counterattack the jewel of fencing.

Source: Akademia Szermierzy, the Light of Life.

Counterattacks are however very difficult. They are very difficult because in that short timeframe between the launch of the attack and the opponent hitting you, you must achieve a simultaneous defence and attack of your own. The two most typical ways to do this in safety is with either a void1 , or with opposition2.

The counterattack works because the opponent must close distance with you in order to deliver their attack. This means that as they attack, they make themselves vulnerable at the same time by bringing their body within the reach of your weapon. Further, if they fence with a single weapon (Longsword, single rapier, etc), then their commitment to the attack also means that for the timeframe of their attack they are generally unable to use their weapon to defend. It is difficult to abort a fully committed attack into a parry if you are suddenly threatened when your attack is in progress. So the opponent both brings themselves within your reach and commits their weapon to a movement which means that they will have difficulties being able to use it to defend for a time.

Sounds like a great time to attack, yes? There’s only one problem: You yourself are about to get hit by a sword also.

I will repeat myself for emphasis: If the opponent has judged their distance and executed their attack correctly, then at the end of its timeframe you will be hit. Whatever you do within your available time for action must prevent that hit from completing.

The alternative, of course, is to accept getting hit.

I don’t know, seems to me like getting hit is a bad idea.

The fundamental challenge of the counterattack is to achieve both your attack and your defence within the timeframe available to you before you get hit. This often requires attacking and defending simultaneously, such as when one voids their threatened leg and strikes the opponent’s head at the same time.

In my experience, counterattacks are usually safest and most effective when the opponent has made an error. The most typical are errors in distance, such as beginning their attack from too far away, or errors in execution, such as drawing their sword back and exposing an arm while within striking range. These errors typically delay the opponent’s hit, and therefore leave more time for you to carry out your counterattack in safety. A counterattack carried out in this way is sometimes called a stop hit or a stop thrust.

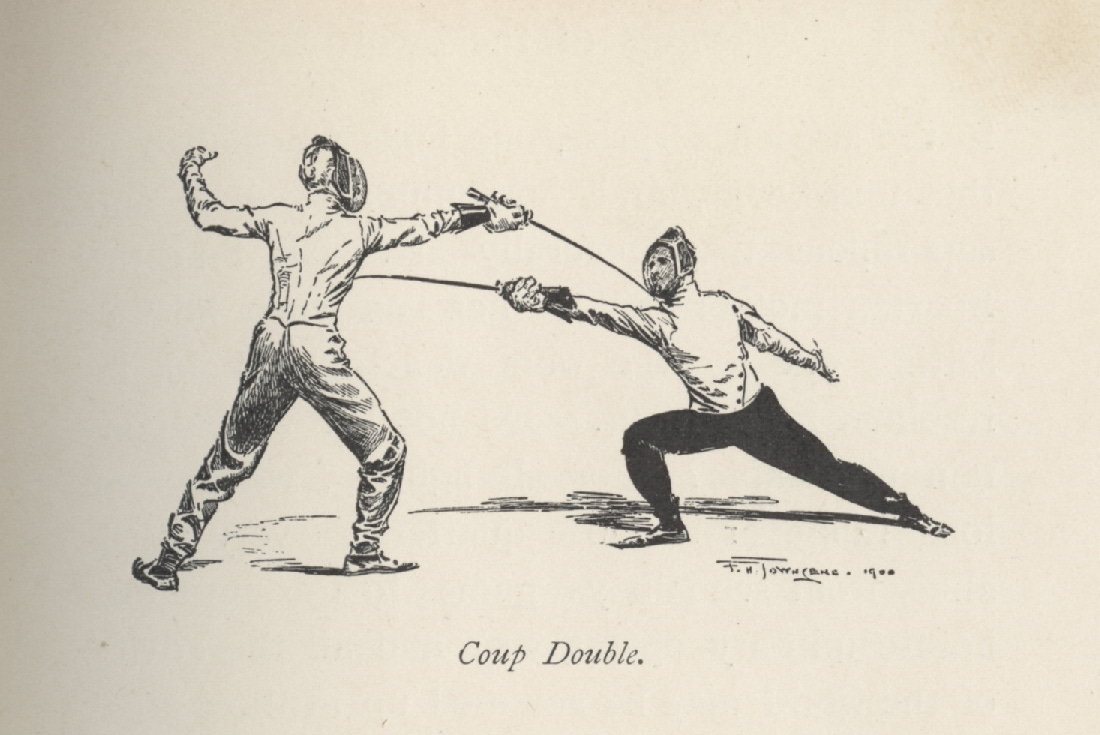

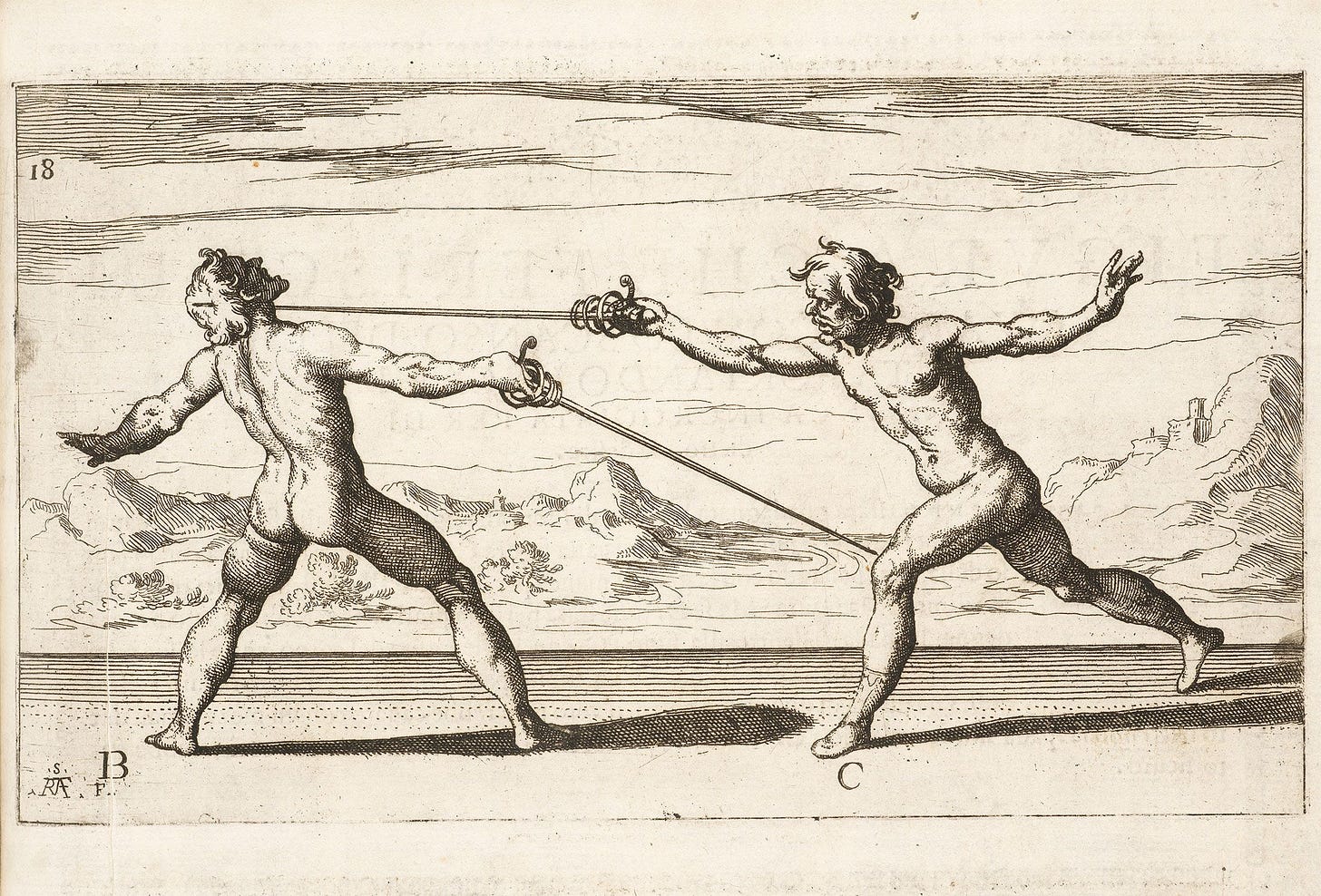

A stop hit combined with a backward slip out of distance.

Two examples of stop-thrusts with blade opposition.

One 19th century French fencer, the Baron de Bazancourt, explains this well in his 1862 work Secrets of the Sword:

“Let me explain before going on. There is a distinction to be made between stop thrusts, and time thrusts. The stop thrust is taken, when your opponent advances incautiously, or when he draws back his arm while executing a complicated attack, whenever in fact he makes a movement which leaves him exposed. The time thrust on the other hand, correctly speaking, is a parry of opposition,—the most dangerous of all parries, for if it fails it leaves you absolutely exposed and at the mercy of your opponent. I have seen it taught in the lesson by every master (as an exercise no doubt), but I have hardly ever seen a master put it into practice in the assault. The [time] thrust has nothing to recommend it, but on the contrary it is to be condemned on many grounds. I should like to see it ignominiously expelled from the fencing room, as the buyers and sellers were expelled from the temple.

“Do you follow the distinction? A time thrust is taken on the final movement of an attack, when you think you know exactly what is coming, and can judge with certainty in what line the point will be delivered. Very well, then parry instead of timing; for if you are wrong—and who is not sometimes?—you can at any rate have recourse to another parry. Whereas the time thrust, when misjudged, results in a mutual hit, and for one that is good tender how much base metal you will put into circulation. The stop thrust, which is taken, as I have said, on the opponent’s advance, is less dangerous.”3

What Bazancourt calls time thrusts are what we might call the “true counterattack”, delivered within the timeframe of the opponent’s properly executed attack. Bazancourt, concerned both with the sport of fencing in his time and with training for the duel with the sharp epee, strongly disliked such counterattacks, finding them too difficult and too unreliable, and if they fail they leave you exposed to the opponent’s point.

So much for counterattacks. What then is a “late counterattack”?

Simply this: When the defending fencer delays until the last possible moment within the timeframe of the opponent’s attack, and then strikes to any available target, heedless of the threat of the incoming blade.

The key problem here in my opinion is the delayed response.

At a certain point in the time window before your opponent hits you, it is possible to still hit them but you will not have sufficient time left to also defend yourself by opposition, void, or any other means. So you can hit, but you often don’t have time left to hit and defend simultaneously.

You will often succeed in landing the hit if you do this, it is true. The lateness of the counterattack which makes it difficult for you to both hit and defend in the available time also means it is extremely difficult for the opponent to defend such a counterattack. The opponent’s blade can only be in one place at a time, can only cover one line at a time, can only attack along one trajectory at a time. Hitting them wherever their sword isn’t is simplicity itself, indeed much easier than trying to attack and defend. So yes, you will often land the hit this way.

But at what cost? If you wish to train as if your training will be put to the test of sharp steel, then accepting being struck by sharp steel simply to get any hit at all is hardly a wise choice. If that’s not your interest and only the sport side of HEMA interests you, under most tournament rulesets the double hit is a bad outcome, and some tournaments will impose double loss conditions if you double repeatedly!

Now I can hear an objection rising from some already, “But if I am going to be hit and I have little time available to respond, shouldn’t I hit them back? Isn’t it better to hit them mutually than to just be hit cleanly by them?”

Very well, let us assume that you are imminently about to be hit. If you are in that situation, then try to parry instead. At least if you try a parry you might escape un-hit, as opposed to the late counterattack which makes receiving the hit almost a certainty.

In my opinion the late counterattack is a very bad habit in every respect. What then can be done about it?

Training Aspects

It should first of all be admitted that some mutual hits which look a lot like late counterattacks arise from the kind of genuine human errors that simply are inherent to the learning process.

How many times have I tried to make a parry or a void or use opposition or otherwise do something sensible, and messed up and got hit, and still hit the opponent anyways? Lots and lots of times! The fencer in that case is not making a late counterattack of the kind this article is decrying specifically, but rather is trying to do something proper but instead just makes a mistake. Mistakes are fine, that’s part of learning.

However, I often observe that some students are simply so desperate to land any touch in sparring at all that they would rather double with late counterattacks than try to fence properly and likely lose without landing any hits at all. The feeling of landing a hit is a reward to them, it feels like winning, even if a trained and sensible fencer can clearly see that the student is making very bad decisions indeed.

Training these students out of this habit is one of our responsibilities as teachers.

I can’t stress this enough for every new fencer who might be out there reading this: You are not winning when you hit an opponent with late counterattacks. You are accepting being hit (Which in sharps means you are rolling the dice and may be receiving a wound which maims or kills you) to give one back. The winning scenario in fencing is to strike without being struck in return, to give and not to receive.

So the first thing in my opinion is to explain and emphasize to our students that simply hitting in and of itself is not the aim of fencing. Fencing is all about how we land the strike. My own aim in my fencing is to fence to create a situation where I can deliver a hit in the maximum degree of safety with the minimum degree of risk possible. That is likewise what I try to teach my students.

The second thing is to build this understanding and aim into your training for all students. How shall we do this?

I have three suggestions on this matter:

Use Priority Rules

One time-tested means is to use priority (or, “right of way”) rules in your practice.

Now I’m not here to re-adjudicate HEMA’s many disputes about priority rules in competition. But I am going to recommend them as a training tool for addressing the specific issue of late counterattacks in your club training.

Much has been written priority rules in HEMA, some good and some bad. Here is the explanation and mindset I use about priority for my own instruction

Priority is a tool for adjudicating who is right and who is wrong in a mutual hit.

Priority is not used in any clean hit. Priority rules are not applicable or necessary so long as the fencing is clean. If I am fencing a partner, I give him a clean hit on the arm and then escape untouched by him, there is no need to apply a priority rule, I simply hit and he did not, therefore the point is mine.

Priority is applied when both fencers hit each other, in order to identify whose action was correct and whose action was incorrect. Or, if you prefer, who was more incorrect than the other?

I can already hear your objection: “But in a double hit they both die, they are both wrong”.

Maybe so. But we are not discussing now the results of competitions or tactics for a duel, we are discussing how to train people to make sound decisions in fencing. This requires both incentives for correct behaviour and disincentives for incorrect behaviour.

When you have a newer or less experienced fencer facing the more experienced members of your club, they will often think: “Well this opponent is certainly going to beat me, but at least if I double him over and over again it’s a neutral outcome, we will have a draw, which is better than me just losing straight out”.

If on the other hand you use a priority convention, that fencer doubling over and over again can still lose that match. It’s not a neutral outcome or a draw, they just lose by repeatedly doubling without properly defending. We change the outcomes and thus we change the incentive structure.

Tied to this is that you ought to have judges for your bouting at your club, or use judging in your drilling and exercises as well. While priority rules can be self-applied by the fencers, it is often better to have a neutral third party watching the match and adjudicating the results of exchanges from an outside perspective.4

The goal here is, again, for the student to understand that doubling via a late counterattack is a loss to themselves, that the hit they land is of little value if they themselves are also being hit by an attack they ought to have defended. We want to nudge these students towards learning to defend as well as attack, and build habits of sound defence rather than risky and dangerous counterattacks in bad times and situations.

The other benefit here is that priority rules can be made very flexible. There’s various ways to set and apply priority, which you as the instructor can use to nudge fencer behaviour and learning in different directions to address different concerns.

In the specific case of late counterattacks, you could for instance use sequence-based priority. In such a convention, the (properly executed) first attack has priority over the counterattack. So if the opponent initiates an attack first, the fencer must do something defensive before they can strike back, or else must interrupt that attack in a clean fashion (Again, void and opposition and other such tools). Simply counterattacking into the attack in the fashion this article is condemning will result in the point being lost to the attack with priority.

This does require that your judges at the club have a consistent definition of what the attack and counterattack are, and apply decisions based on that in a reasonably consistent fashion, which is admittedly challenging in itself. Nothing is ever simple in fencing, is it? But we are discussing training here, not competition, so the stakes of judging in this case are lower and if it takes some time for your club to develop good judging skill, well that’s okay too.

Let us consider a different example: Perhaps you are concerned that your students are taking hits in deep targets (Head and body) and doubling their opponents shallow (Arm or leg). In that case, you might try training them under target-based priority. Such a rule might be that a hit to the deep target has priority over a hit to the shallow target, so ignoring that thrust to the chest to slash the leg will still result in a loss for the fencer.

Target-based priority alone can have some peculiar effects on fencing (i.e: Ignoring a strike at your hand to thrust the opponent in the chest), so I would recommend combining it with some type of sequence-based priority as well.

There’s countless different ways to use priority rules, and different ways to set them for different objectives. Experiment with them, try different things, find what works well for you and for your fencers. The other great thing about priority in training is that unlike a competition you can change priority rules across different sessions or even different drills, so that your students are always fencing under different constraints and rulesets to develop more well-rounded skillsets.

Consistent judging of strike quality

One habit that I have often observed in HEMA is that people have extremely stringent criteria about the quality of a strike in an attack, but incredibly lax criteria for the quality of a strike in an afterblow or a mutual hit.

The assumption is often that the attacker needs to be making some picture-perfect, cleave-a-man-in-twain cut for their attack to count, but the defender need merely brush or slap the attacker anywhere with their blade in any lazy fashion to land an “afterblow” and neutralize the value of the attack.

As we discussed above, some students will feel that the “neutral” outcome of a double loss is the best they can hope for, so for them that’s the win condition. If your club accepts double hits with extremely lax and permissive strike quality, then it will be very easy for them to double.

As I have discussed previously, doubling is easy in general terms. Doubling with any kind of blade contact at all is even easier. Another way we can change this incentive structure is by making it harder for the late counterattack to be scored using quality rules.

Your standards for accepting a double hit as a valid strike should be consistent with your standards for accepting an attack as a valid strike. So for example, if you don’t accept flat hits as valid, then if the opponent does a late counterattack and lands flat then that strike should be thrown out.

This can be implemented by fencers in their bouting, and I would strongly recommend that the instructor lead by example in this matter. So when you are bouting a student and you happen to land an afterblow or a double hit, and you think it’s flat or it lacked structure or intentionality, then admit so! Tell them “Nah my hit was flat, your point”. It is good for the instructor to model honesty and humility in your training.

But as with priority rules, I think this is best done with a judging partner as a neutral third party observing from the outside and telling the fencers what happened. This is more reliable than fencers doing the judging themselves as a general matter, and is good for building your club’s judging skill as well.

More stringent criteria for all strikes will make the late counterattack a more difficult option to be counted as a valid strike, which should reduce its appeal to your newer fencers. But a fencer can still make late counterattacks with the edge or point and good striking form. So I do recommend combining strike quality rules with your priority rules to more fully and completely disincentivize the late counterattack.

Teach complete tactics and techniques

What do I mean by complete techniques?

Simply this: Don’t teach your students “offensive” techniques or “defensive” techniques or tactics in separate boxes. Teach them to think of both offence and defence together.

This does not necessarily mean the mythical and very difficult single time attack with opposition. If you can pull that off, great for you, but there are simpler ways to achieve this concept as well.

Here is a example of what I mean from a competition I attended recently:

In this sequence, I cut to the opponent’s arm, then parry their cut around, and parry again to their final strike as I back out. My actions in this exchange had both offensive elements (my cut to their arm) and defensive elements (My parrying and my retreat out).

So when you are teaching your students tactics and techniques for fencing, whatever teaching approach you use or whatever style or source you practice from, I believe you should try to ensure that the student understands both the defensive and the offensive element of every action and every tactic. There should be no offence without defence, nor defence without offence. Every parry has a riposte, and every attack should also have an element of defence to support your safety in the engagement as well.

Here I use a stop cut to my opponent’s exposed arm in their attack, followed immediately by recovering with a step back and a parry.

In particular when it comes to using counterattacks, the element of safety generally requires that the opponent commit an error in the execution of their attack. If they expose a hand or arm early in the attack, or if they step within range without extending their blade, or if they attack from too far away, or other such errors in the execution of their attack, then you will have an opportunity to make a safe counterattack yourself. The error is generally one which creates a vulnerability or delays or slows down their threat, such that you have time and opportunity to both hit and make a defensive action yourself.

So when teaching your students about counterattacks, in my opinion you should be teaching them to look for or trying to create errors in the opponent’s attack which can be exploited for a counterattack. Then you are teaching the counterattack in a complete fashion, not just hitting the opponent but hitting them while maximizing our own safety. If no such error exists, the counterattack becomes exceedingly difficult and risky and it is usually safer and more reliable to parry-riposte or defend by distance (or both) instead.

At a certain level of fencing strategy and pedagogy as well, offensive and defensive movements become indistinguishable anyways5. So regardless of whether you’re teaching counterattacks or anything else, you should always be teaching both the offensive idea and the defensive idea together. Every time you teach an attack, you should be asking “How can we create safety for the fencer in this attacking situation?”, and every time you teach a defence you should also be asking “How can the fencer use this defence to set up a threat to the opponent?”.

Conclusions

Late counterattacks are a very bad habit in a fencer. They’re dangerous if you wish to learn fencing suitable to sharp combat, and they’re disadvantageous to the competitor in sports as well.

However, for as much as I am strongly against them, I should reiterate that doubles are to some extent a natural part of the learning process for the student. When students are trying out new ideas or new techniques, particularly more complex and challenging ones like the counterattack, they will make mistakes and some of those mistakes will result in mutual hits.

As instructors, we shouldn’t worry ourselves too much that our students make mistakes. Don’t agonize that your students double from time to time, that’s really not useful and only causes you anguish. Instead we should concern ourselves with ensuring that students learn from their errors and gain greater skill over time.

I’ve provided some suggestions for training in this article to help address the problem of late counterattacks, but as always bear in mind that I am just one fencer, just one instructor, and that I am no master. The suggestions I have made above have proven useful to me at my club, but you should try things out for yourself. Experiment, observe, find what works best for you and your students. And if you find good new solutions to this problem, come and tell me because I would love to hear about it and learn from you as well!

Moving the body part under attack out of the way and then striking the opponent after their blow has passed you by

Blocking the opponent’s sword at the same moment that you strike them. See the Kunst des Fechtens Absetzen for an example, although Absetzen can be done as a parry-riposte as well.

I recommend making students drill in groups of three, with two fencers practicing the exercise and the third judging. The two fencers do a set number of points or exchanges, then the judge rotates into fencing and another fencer becomes the judge. This way all your students always practice judging alongside fencing. That judge role is also beneficial in that students are made to consciously observe what others are doing, and will learn from the successes and errors of others.

Johan Harmenberg, Epee 2.6, pg. 85